By John Gullion

Cy Slapnicka had been in the game 29 years in the summer of 1935 when he finally cemented his place in history.

According to Brian McKenna, writing for SABR, he was a pitcher with a below-average fastball and an above-average curve. The Iowan of Bohemian descent spent most of his playing days knocking around in the minors and building a series of grudges against the system that bounced him around the Midwest, from Louisville to Milwaukee – where the club balked at his sideline career as a strongman/acrobat/juggler – to Birmingham, Alabama.

Slapnicka managed two brief stints in the minors – first with the Cubs in 1911 and again with the Pirates in 1918. For his career, he appeared in 10 games in the majors, going 1 and 6 with a 4.30 ERA. He struck out 13 in 73.1 innings pitched. He went the distance in half of his career eight starts and once, in 1911, pitched eight innings of relief against Honus Wagner’s Pirates. His lone win was a 10-4 decision on July 5, 1918 over the Giants. He was the hard-luck loser 13 days later, going 13 innings in a 2-1 loss to the Phillies. McKenna writes that Slapnicka’s 15-year career ended at the tail end of the 1920 season as he pitched for the Cedar Rapids Rabbits and split time working at a local men’s store.

It was the next year that his real career in baseball began. The Indians named him a scout and – McKenna says – he became one of the best known, most traveled scouts in the business. Over the course of his career – which included a brief managing stint in the Cotton States League and a six-year run as the Indians General Manager – he signed such future standouts as Lou Boudreau, Hal Trosky, Bobby Avila and Roger Maris.

But the signing that made Slapnicka famous and secured his legacy in the game? It was a teenage phenom who lived about 150 miles from his native Cedar Rapids. A pitcher he found based on a tip from an umpire. A pitcher named Bob Feller.

After dominating for his high school in Van Meter, Iowa, Feller began pitching for the semi-pro Farmers Union team in Des Moines, according to C. Paul Rogers III, writing for SABR. That September, Feller and the Farmers went to a tournament in Dayton, Ohio that left the assembled scouts drooling. Suddenly, Feller – who’d just finished his sophomore season in high school – was receiving offers with significant bonuses.

Which one did he take?

None of them. Slapnicka had secretly signed him months before for a dollar and an autographed ball that Feller later said was signed by all the Cleveland Indians.

"This was a kid pitcher I had to get,” Slapnicka was quoted as saying. “I knew he was something special. His fastball was fast and fuzzy; it didn't go in a straight line; it would wiggle and shoot around. I didn't know then that he was smart and had the heart of a lion, but I knew that I was looking at an arm the likes of which you see only once in a lifetime."

Prior to the implementation of the draft in the 1960s, minor league baseball signing and scouting was the Wild West with scouts fighting to be the first to sign players or stash them away so others couldn’t get to them. Slapnicka was hardly alone in running afoul of the rules, but he was one of the most infamous scouts of the time, being called into commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis’ office on multiple occasions.

The idea – such as It was – was for Feller to go to Fargo-Moorhead the following spring – after finishing his junior season. But his arm got sore and the Indians transferred his contract to the New Orleans Pelicans, a potentially wild swing in fortunes for a teenage professional baseball player. Rogers says Feller was placed on the “voluntarily-retired” list while he finished his spring semester at Van Meter.

Feller never made an appearance for the Pelicans. The Indians brought him to Cleveland to “work concessions” and arranged for him to pitch for a local semi-pro team. He made his first official Major League appearance on July 19, 1936 at the age of 17. He pitched 62 innings that first season, going 5-3 with a 3.34 ERA. He struck out 76 and allowed 52 hits and 47 walks.

After going back to Iowa to finish high school, he returned to the majors in ’37 as an 18-year-old. He earned an All-Star Game spot in 1939 and established himself as one of the best players in the game. He finished third, second and third in MVP voting in 1939, ‘40 and ‘41.

The rest is pretty well-known. Feller enlisted in the Navy days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Not content to sit out the war doing physical training, he was assigned to the USS Alabama which first guarded ships in the Northern Atlantic then was sent to the Pacific.

"I told them I wanted to ... get into combat; wanted to do something besides standing around handing out balls and bats and making ball fields out of coral reefs," Feller said.

While serving on the Alabama, he was decorated with six campaign ribbons and eight battle stars.

Feller gave up almost four prime years of his career to serve. He missed all of ‘42, ‘43 and ‘44 when he was 23, 24 and 25 years old respectively. He returned for a handful of games in ‘45, making his full season return in ‘46 at the age of 27.

Feller made sure the baseball world knew he hadn’t lost a thing off his famous blazing fastball and let them know he’d added a slider. He embarked on a season for the ages, going 26-15 with a 2.18 ERA. He started 42 games and went the distance in 36 of them. He pitched 371.1 innings and set the major league record for strikeouts with 348. He finished sixth in MVP voting that season, even though Cleveland went an ugly 68-86-2. You want to get a feel for how voting went back then? Feller finished behind MVP Ted Williams and two of his Boston teammates – Bobby Doerr and Johnny Pesky – as well as Detroit pitcher Hal Newhouser and Washington National first baseman Mickey Vernon. Williams, Vernon and Newhouser were all deserving, but the Boston influence was heavy. In all, the Red Sox had seven players finish in the top 13 in voting. The Sox went 104-50-2 that season but lost to a loaded Cardinals team.

Feller remained a dominant force into the ‘50s and pitched his last in 1956, at the age of 37…20 years after he’d made his Major League debut.

Feller’s place in the game’s history – as a player – is firmly secure. But let’s go back to the 1930s and Mr. Slapnicka, whose shenanigans nearly cost the Indians the chance to keep the future Hall of Famer. At the end of the 1936 season, Feller and his father were called to Landis’ office after a complaint was filed by the owner of the Des Moines Club. Both Fellers told Landis they wanted to stay with the Indians (although from the prospective of 90-years-later, had really lowballed the kid!). The Commissioner eventually relented, and the Indians paid a $7,500 fine to the Des Moines team.

Why was Feller so intent on staying with the Indians? It appears it was his relationship with Slapnicka, who was promoted to Indians General Manager in 1936. According to McKenna, in January of 1937, Feller re-signed with the Indians and named Slapnicka his Manager which seems a colossal conflict of interest. Slapnicka handled his young star’s finances and endorsements briefly, but their relationship was far stronger. Feller frequently cited Slapnicka as a father figure.

And so, we come to the relationship between a great scout and a great ballplayer. How much did the scout share with his protégé? While Feller worked around the game doing commentary and as the first President of the Player’s Association, he never got into the field work that his mentor did.

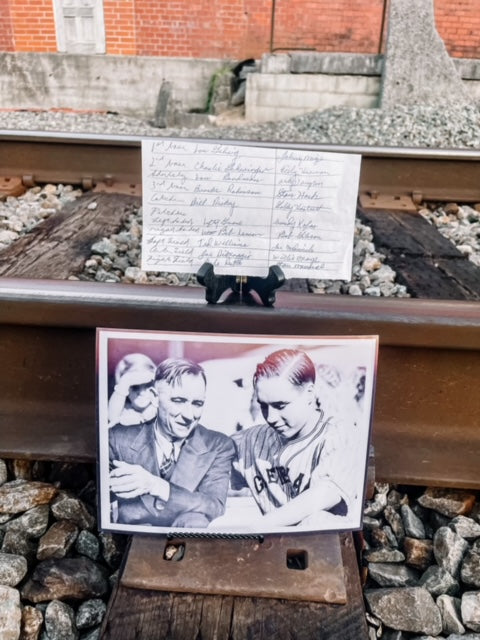

Still, Feller had an eye for talent. A fact proven by something in the Bob Feller display at the GroveWood Baseball Museum. At some point in the late ’80s or early ’90s, the legendary Feller was asked to list the best players he’d ever seen play. And so, he provided a well-thought-out list of two players at each position. Not surprisingly, it is heavy with his peers, players who were at the height of their powers in the mid-to-late 30s are well-represented on his list. There are a couple of deeper cuts, but almost everyone on the list is in the Hall of Fame. There aren’t a lot of players listed who came after Feller, but that’s not terribly shocking…Feller had a well-earned reputation for being a bit prickly, a bit of a curmudgeon in his later years.

THE LIST:

First Base

Lou Gehrig – Feller’s first time facing the Yankees in September of 1936 was a disaster, as he gave up five runs in the first inning and was sent to the showers. He walked Gehrig in their only match-up that season. The next time Feller saw Gehrig was in their first meeting of the ’37 season, he plunked the Iron Horse … twice.

Johnny Mize – The Hall of Fame first baseman’s career aligns with Feller’s. The Big Cat was a rookie with the Cardinals in 1936, and, like Feller, also lost three seasons to war service. Mize went on to play for the Giants and the Yankees, earning his tenth and final All-Star appearance at the age of 40 in 1953.

Second Base

Charlie Gehringer – Gehringer was already a legend by the time Feller arrived in the Bigs in 1936, but the “Mechanical Man” still had it. He won the AL MVP in 1937 at the age of 34. The 17-year-old Feller got the Hall of Famer to fly out to center in a relief appearance in their first match-up on August 3, 1936.

Billy Herman – Herman spent his entire career in the NL playing second base for the Cubs, Dodgers, Braves and Pirates from 1931 to 1947. A 10-time All-Star, the future Hall of Famer missed two seasons while serving in World War II.

Shortstop

Lou Boudreau – Another one of Slapnicka’s finds, Boudreau – who lost his college eligibility at the University of Illinois thanks to a handshake deal with the Indians GM – joined the big league club and became Feller’s teammate in 1938. The Harvey, Illinois native was only 24 when he was named the Indians’ player-manager after the 1941 season, a position the future Hall of Famer held until he was released following the 1950 season, two years after leading the Indians to their last World Series title.

Arky Vaughn – Another career National Leaguer, Vaughn, the future Hall of Famer – played most of his career with the Pirates. A football teammate of future President Richard Nixon in high school, Vaughn starred at shortstop for the Pirates from 1932 through 1941. Moving to the Dodgers, he played two years at third base before retiring after a disagreement with Dodgers manager Leo Durocher. With Durocher suspended for the 1947 season, Arky made a comeback at the age of 35, hitting .325 in 64 games. He returned for the 1948 season and then retired for good. He died, tragically in 1952, when he drowned in a boating incident.

Third Base

Brooks Robinson – Considered by many the greatest third baseman of all time, Brooks Robinson was another teenage phenom. He broke through with the Orioles for six games in 1955 and 15 games in 1956, Feller’s last two seasons in the majors. The two future Hall of Famers never faced each other.

Stan Hack – Maybe the most obscure name on the list, Hack played 16 seasons with the Cubs from 1932 to 1947. A multi-time All-Star, “Smilin’” Stan’s best season was probably 1938 when he hit .320 and had an OBP of .411. He is the first player on the list not in the Hall of Fame.

Catcher

Bill Dickey – Another Hall of Famer who lost years off his career to combat service, Dickey played for the Yankees from 1928 to 1946, earning 11 All-Star appearances and winning 7 World Series titles. His 1936 BA of .362 held the record of highest single-season average by a catcher for 73 years.

Gabby Hartnett – Another long-time Cub on the list, Hartnett played for Chicago from 1922 to 1940, earning an MVP in 1935. Hartnett closed his career in 1941 with the Giants, playing in 64 games and batting an even .300 at the age of 40. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1955.

Left-Handed Pitcher

Lefty Grove – One of the two namesakes for the GroveWood Baseball Museum – Grove was different than Feller in a lot of respects. He didn’t break through into the majors until 1925 when he was 25 years old. But there were a few similarities as well. While he never led the league in innings pitched, Grove often approached the 300 innings mark in his younger days with the Athletics. He led the league in strikeouts in his first seven seasons, earning MVP in 1931. Later in his career, while with the Red Sox, although he didn’t pitch as many innings, he racked up more than 100 strikeouts three more times before retiring in 1941. The two future Hall of Famers’ first meeting came on August 1, 1939. Feller lasted six innings, allowing six runs while Grove went the distance and picked up the 7-5 win.

Sandy Koufax – Another phenom who entered the majors as a teenager. Koufax broke through in 1955. Like Robinson, the beginning of his career barely overlapped with the end of Feller’s. The life-long Dodger and future Hall of Famer pitched 12 seasons from 1955-1966.

Right-Handed Pitcher

Bob Lemon – A post-war teammate of Feller’s, Lemon broke through as a utility player, with nine total plate appearances in 1941 and 1942 before missing most of the next four years due to war-time service. A key part of the Indians’ 1948 World Series title, Lemon was only two years younger than Feller, but did not pitch in the majors until a full decade later. He was the team’s Opening Day starter in centerfield in 1946, and his play in center helped Feller preserve a no-hitter on April 30th of that year. Lemon hadn’t pitched much previously, but his lack of hitting and his strong arm led to the Indians giving it a try. In his first full season as a pitcher, the Indians won the World Series.

Bob Gibson – The first player on the list whose career did not overlap with Feller’s, Gibson was a famously-intimidating presence on the mound. Pitching for the Cardinals from 1959 to 1975, Gibson – like Feller – ate up innings on the mound, twice crossing the 300-inning threshold in a season. In 1968, at the age of 32, Gibson was the MVP and Cy Young Award winner. He struck out 268 batters, won 22 games and had an insane 1.12 ERA. His season – along with Tigers starter Denny McLain - led Major League Baseball to change the height of the mound.

Left Field

Ted Williams – The Splendid Splinter. What more do we need to say? In Feller’s best year, Williams took home the MVP award.

Joe Medwick -Ducky Medwick is a Hall of Famer who earned MVP for the Cardinals in 1937 – Feller seems fond of players who were stars when he was young in the league. Over his 17 seasons with the Cardinals, Dodgers, Giants and Braves, Medwick batted .324 and slugged .505.

Center Field

Joe DiMaggio – Joltin’ Joe broke through in 1936, same as Feller, and Feller would have a front-row seat as Joe won three MVP Awards over the next 12 seasons. Feller also would have had a front-row seat to the end of DiMaggio’s famous 56-game hitting streak 1941. The Indians – with some nifty play from Boudreau – ended the streak on July 17th. The next day, July 18? DiMaggio got two hits off Feller, but Feller went the distance in a 2-1 win.

Willie Mays – Another teenage phenom, Mays broke through with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro League in 1948 at the age of 17. He made his Major League debut in 1951, winning Rookie of the Year. After missing 1953 due to military service, Mays won his first MVP in 1954, and Mays’ and Feller’s teams met one another in the World Series. Despite having gone 13-3 in 19 starts in the regular season, Indians manager Al Lopez didn’t get Feller into a game in the series. The Indians had won 111 games that year, but yet were swept by the 97-win Giants. In Game One of the Series, Mays made his famous “Catch”, robbing Vic Wertz with an over-the-shoulder grab in the cavernous Polo Grounds centerfield. It is one of the best-known plays in the history of the game and a play that the famously-prickly Feller downplayed in an interview with the Plain Dealer decades later.

Right field

Babe Ruth – The second player on the list whose career did not overlap with Feller’s at all, Ruth’s last season with the Braves was a handful of games in 1935. How honest was Feller being to the exercise here? It’s hard to say. While the men didn’t play against each other in the Majors, it’s possible the kid from Iowa caught a game in which Ruth played at some point. Or, maybe during a barnstorming tour?

Stan Musial – Stan the Man spent his entire career from 1941 to 1963 in the NL with the Cardinals, losing a year in 1945 to military service. Musial was a three-time MVP who finished second in voting four times and was a 24-time All-Star. With a career average of .331 and a career slugging percentage of .559, Musial finished just shy of the 500-Home Run Club and is widely-considered among the greatest hitters in the game’s history.