Written by John Gullion

It’s easy – as we marvel at the triple-digit, video-game numbers that modern pitchers routinely post – to forget the velocity now in baseball is not a modern invention.

It’s probably more common today, but advances in focus, technology and method in tracking pitchers’ velo has made it more difficult than ever to compare power-pitching through the ages.

Is Ben Joyce throwing harder than pitchers of yesteryear? The numbers say so. However, we can trace the lineage of pitching gas back through Randy Johnson and Nolan Ryan, through Bob Gibson and Satchel Paige, through Bob Feller, all the way back to Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood.

Whatever era, there is a danger that goes with throwing that hard. A risk for each batter who steps in trusting that either the pitcher won’t come in too high or that his own reflexes will be good enough to avoid tragedy if one gets away from the hurler.

Which brings us first to Ray Chapman – the only major leaguer to die from being struck by a pitch.

It was August 16, 1920, and Chapman’s Indians were visiting the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. On the mound was Carl Mays – a submariner whose stats say belongs in the Hall of Fame, but was never enshrined. Mays had started his career as a traditional hard-throwing righty, but had to change his throwing motion following a shoulder injury. How hard was Mays throwing that day in Cleveland? It’s hard to say. But after the injury, he was known for the movement created by his knuckle-scrapping throwing motion, not his power.

That day in New York, the visitors were up 3-0 in the fifth when Chapman – who was known for crowding the plate – shifted in the box as if to bunt. Mays – as he was coached – automatically switched from low fastball to something up and inside. Chapman – a well-liked shortstop – was unable to avoid the pitch, which may have had a little bit extra movement after a directive from the league office that umpires were going through too many baseballs and should leave balls with minor scratches or abrasions in. Whatever the issue, the ball struck Chapman in the left temple, making a cracking sound as if the ball had hit a bat.

Chapman crumpled to the ground while Mays fielded the ball – which had bounced back to the mound – thinking it had hit the bat. Doctors were summoned and Chapman was revived. He tried to walk off the field, to the clubhouse in center. He collapsed at second and was carried to further medical attention. Doctors tried to save Chapman – who was newly married and had a young child. But attempts were unsuccessful.

Thankfully, it was the first – and only - time a major leaguer died from being struck by a pitch. But it was not the first time a major leaguer had a close call.

June 15, 1894, slick fielding shortstop Bob Allen - playing for the Phillies in a blowout 21-8 win over Cincinnati - stepped to the plate against Icebox Chamberlain and took a ball to the face, fracturing his orbital bone and eye socket. He was hospitalized, and there were fears he would succumb to his injuries or be left blind.

Allen eventually recovered, but left the game for quite a while, returning in 1897 with the Beaneaters. He was never the same player, then tried to make his way as a manager, and eventually ended up as a minor-league owner of the Knoxville Smokies from 1932 to his death in ’43.

At one time, Allen was thought to be the key to championships for the Phillies under Harry Wright – an English Cricketer who had traveled across the pond and was known as the father of professional baseball. The future Hall of Famer Wright had built up a considerable reputation, but his tenure in Philadelphia was underwhelming. After an 1889 season in which his middle infield defense had played abysmally following the departure Arthur Irwin to become the player/manager of the Washington Nationals, Wright – and the Phillies ownership team of Al Reach and John Rogers – were looking for help.

They turned to Eddie Fusselback, a native Philadelphian who’d had a couple of seasons playing “major league” ball in the American and Union Association. Fusselback spent the 1889 season in Davenport with Allen, who was called on to be the Hawkeyes player-manager despite the presence of several veterans on the team. Fusselback – whose own career was stunted by a hand injury - was in a unique position to help.

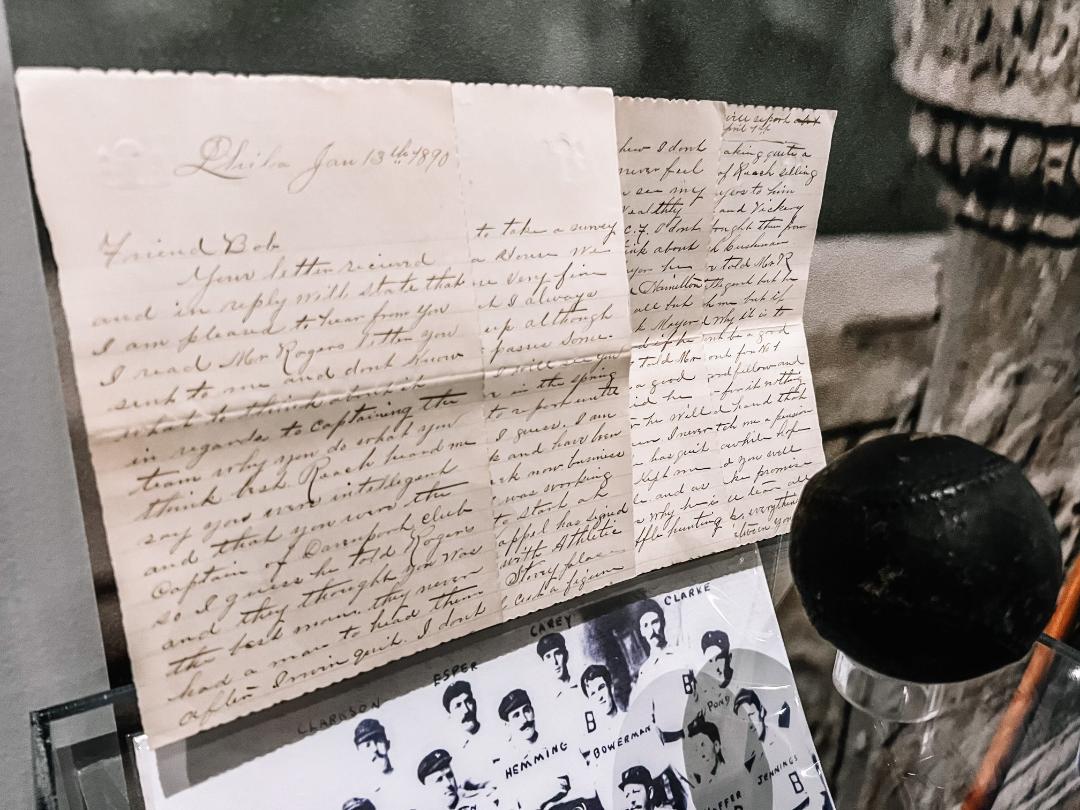

How do we know? Well, in the GroveWood Baseball Museum collection, there is a letter – dated January 1890, in which Fusselback lays out the situation quite candidly to Allen, and also offers advice.

It appears that with the letter, we are joining a conversation – one that took place 134 years ago – midstream. Via context, we can conclude that Allen had forwarded a letter from Reach offering the youngster the team’s shortstop position and captainship.

Over eight pages, four sheets of notepaper written front and back, the catcher writes - with penmanship that is both exquisite and hard to decipher - about the Philadelphia team and its players and management, as well as touching base on some former teammates from Iowa. Fusselback shares – in some detail – the hardships of being a ballplayer at the time. He does a little scouting, a little gossiping, and a little coaching for the benefit of his young friend/protégé.

It is a fascinating relic from the time when professional baseball players tried to start their own splinter league – the Players League only lasted a season but included some of the best players of the day. The letter is – quite literally – inside baseball, a unique historical perspective from a man nearing the end of his professional career to a friend and teammate at the start of his.

“Reach heard me say you’re very intelligent and that you were the Captain of Davenport. I guess he told Rogers that you was (sic) the best man. They never had a man to head them after Irwin quit.”

Fusselback told his friend that he thought the Phillies management was mostly on the up and up—“I don’t think he was giving you taffy in that respect. Although they will swell you on anything to get (them?) to sign a contract.”

Fusselback’s scouting/spy work went beyond speaking with management.

“I talked to (Joe) Mulvey last Sat. and he told me he would do all in his power to help you along. He is a good man will go after anything and you can work with him. I am satisfied (John George) Meyers will help you (as well). They are friends of mine.”

Neither man played for the Phillies that year. Mulvey was third base for the Athletics team in the Players League while Meyers played for the Athletics of the American Association.

Allen wasn’t the only new man for the Phillies in 1890. Future Hall of Famer “Sliding” Billy Hamilton – who set the major league record for runs scored in 1894 – joined a crowded Phillies outfield that season. Fusselback told Allen he expected some changes would be made.

“(Eddie) Burke, he plays centerfield. I don’t know what to think about (Al) McCauley and (Ed) Mayer,” he said. “Mr. Reach has signed Hamilton. He may keep them all, but I doubt it. I think (Al) Meyers will make a second if he is given a (shot?). I told Mr. R to give you all a good show and he said he would. Whether he will remains to be seen.”

Fusselback then offered his up-and-coming friend some advice—“I tell you Bob, it is easier now days to look out for No. 1, but if I like anyone, I would go broke on them but I have had some of the dirtiest tricks done me this winter I have ever had done to me before. Don’t be a good fellow. Look out for No. 1,” he said. “I have been a good fellow and what have I to show for it? Nothing but a battered hand that won’t even fetch me a pension.”

Did Allen take his friend’s advice? We can’t be sure. He pinched in for Wright – who fell ill – and served as player manager in 1890. But even with the Future Hall of Famer Hamilton, the Phillies were little more than also-rans throughout Allen’s time with the club.

The near fatal injury all but ended Allen’s playing career. After trying to make it as a manager, he left the game to make his fortune in the lumber industry before returning as a minor league owner. Fusselback fell out of the game by 1892 and history loses track of him until his death in 1926. He was nearly 70 and had been working as a plumber.

We do know, however, that Allen did not take at least one piece of Fusselback’s advice. At the end of the letter, he wrote the following: “For heaven’s sake, promise me you will tear all my letters up. Everything is confidential between you and I.”